Diagrams in Anthropology

edited by:

Tristan Partridge

Tristan Partridge

“Diagramming is the procedure of abstraction when it is not concerned with reducing the world to an aggregate of objects but, quite the opposite, when it is attending to their genesis…

extracting the relational-qualitative arc of one occasion of experience and systematically depositing it in the world for the next occasion to find… the activity of formation appearing stilled”

(Massumi 2011: 14, 99)

Massumi, B. (2011) Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. Cambridge, Mass. & London, England: The MIT Press.

extracting the relational-qualitative arc of one occasion of experience and systematically depositing it in the world for the next occasion to find… the activity of formation appearing stilled”

(Massumi 2011: 14, 99)

Massumi, B. (2011) Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. Cambridge, Mass. & London, England: The MIT Press.

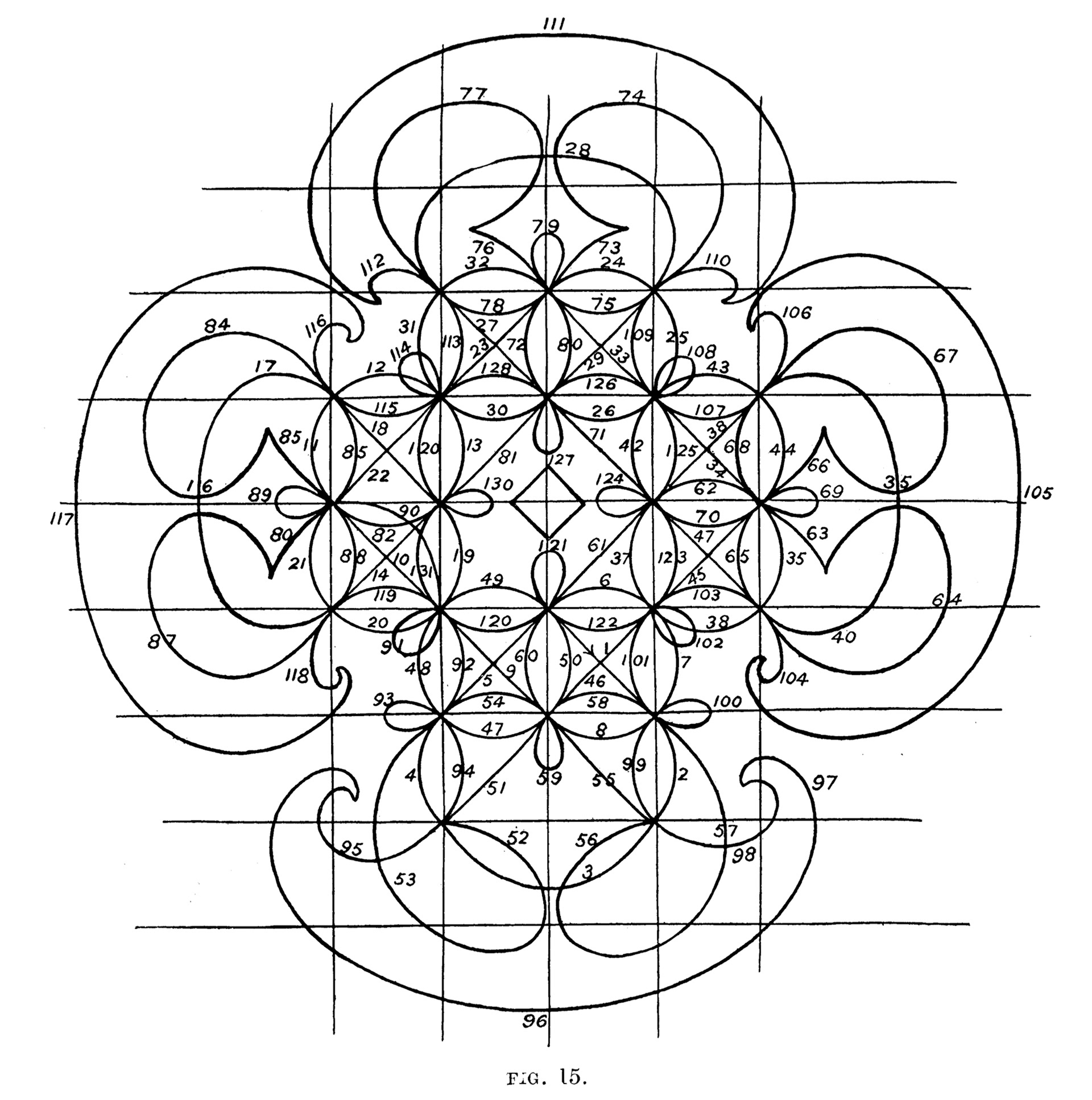

“Wí man bwetewásee: This is a very small black bird with a red head. From Ambrim.”

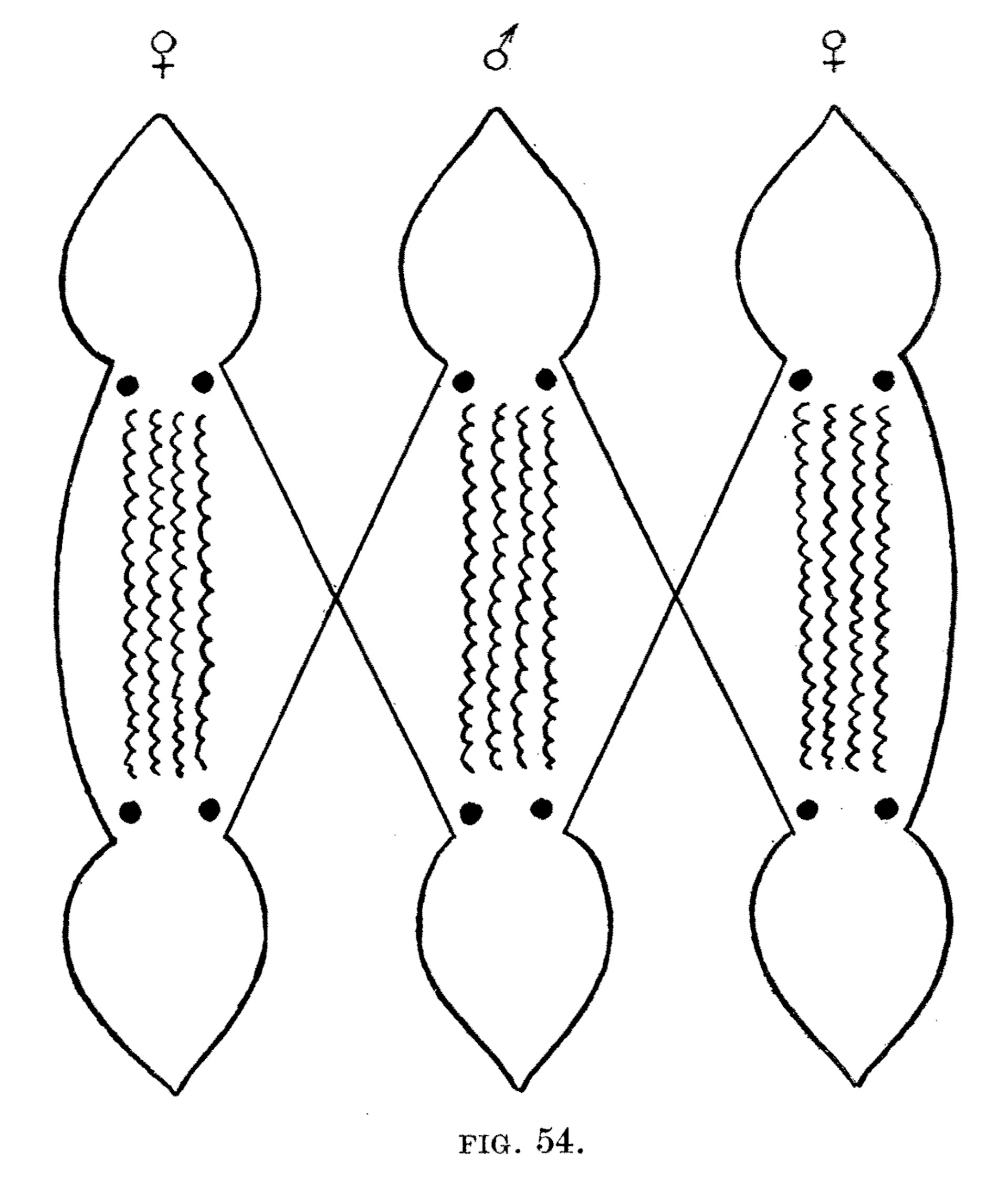

“" Three Ghosts Sleeping." The ghost in the centre is a man; those on either side are women. From Seniang.”

“Netomwar: "Adultery." From Lambumbu or Lagalag.”

"A drop of water falling on a stone"

Deacon, A.B. and Wedgwood, C.H., 1934. Geometrical Drawings from Malekula and Other Islands of the New Hebrides. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 64 (Jan.-Jun.), 129–175.

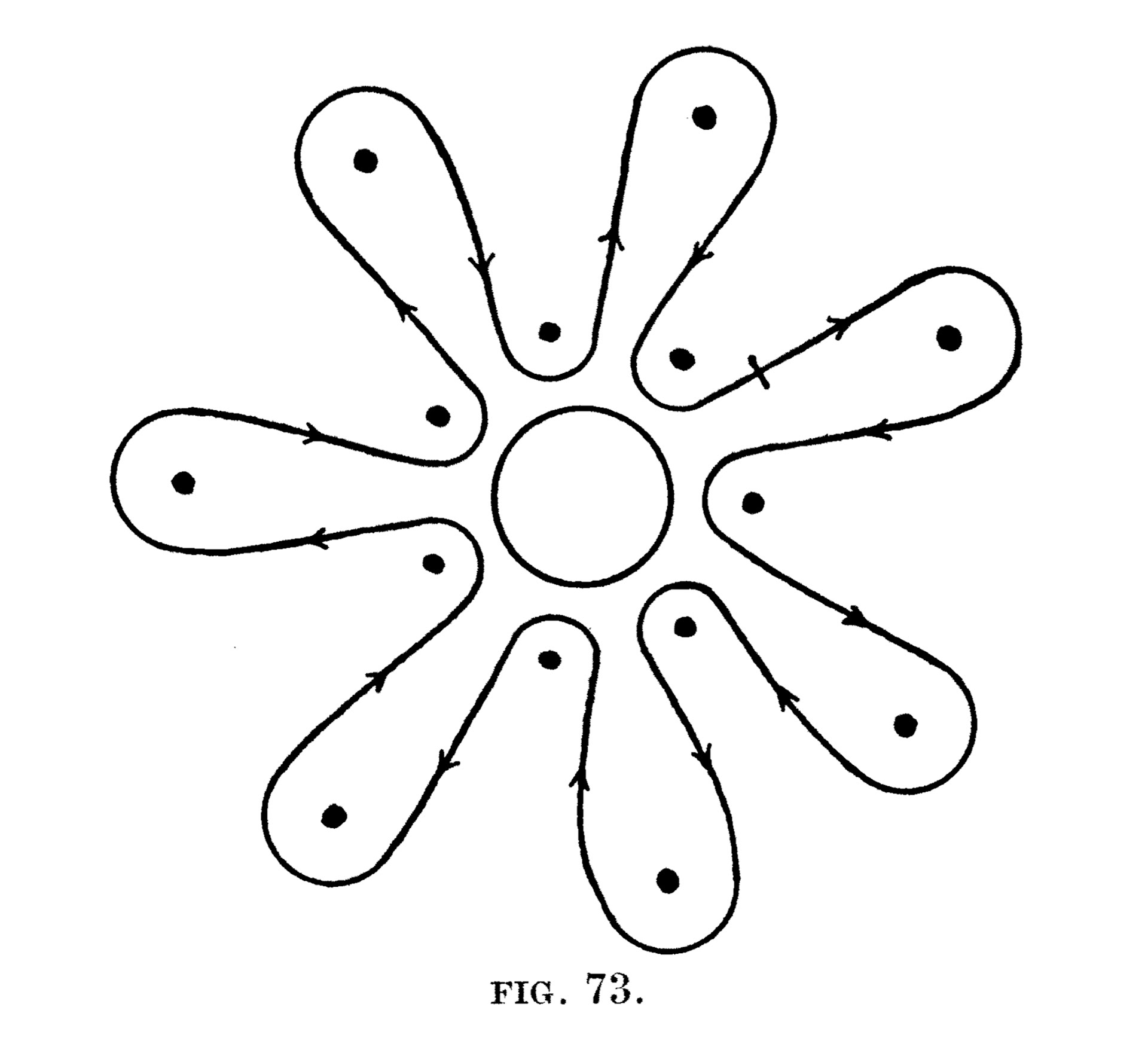

Young, J., 1919. The Paumotu Conception of the Heavens and of Creation. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 28 (4(112)), 209–211.

“The likeness (or description) of things made known to the people of ancient times. The form of this our World and the account of our ancestors, and of the beginning of the movement of animal life. This is the true and succinct description (literally a bundle tied up with a knotted string) of mankind which was confined in narrow spaces, and of the origin of things and of the various trees (or vegetation) and of the bringing forth of animals which suckle their young, such as four-footed animals. These are to be seen in this sheet of paperas understood by the writer, I, Paiore, 1869.”

“The likeness (or description) of things made known to the people of ancient times. The form of this our World and the account of our ancestors, and of the beginning of the movement of animal life. This is the true and succinct description (literally a bundle tied up with a knotted string) of mankind which was confined in narrow spaces, and of the origin of things and of the various trees (or vegetation) and of the bringing forth of animals which suckle their young, such as four-footed animals. These are to be seen in this sheet of paperas understood by the writer, I, Paiore, 1869.”

“The Maori meeting house as an object distributed in space and time."

Neich, R. (1996) Painted Histories. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Neich, R. (1996) Painted Histories. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Godelier, M. & A. Jablonko (1998) “To Find the Baruya Story.”

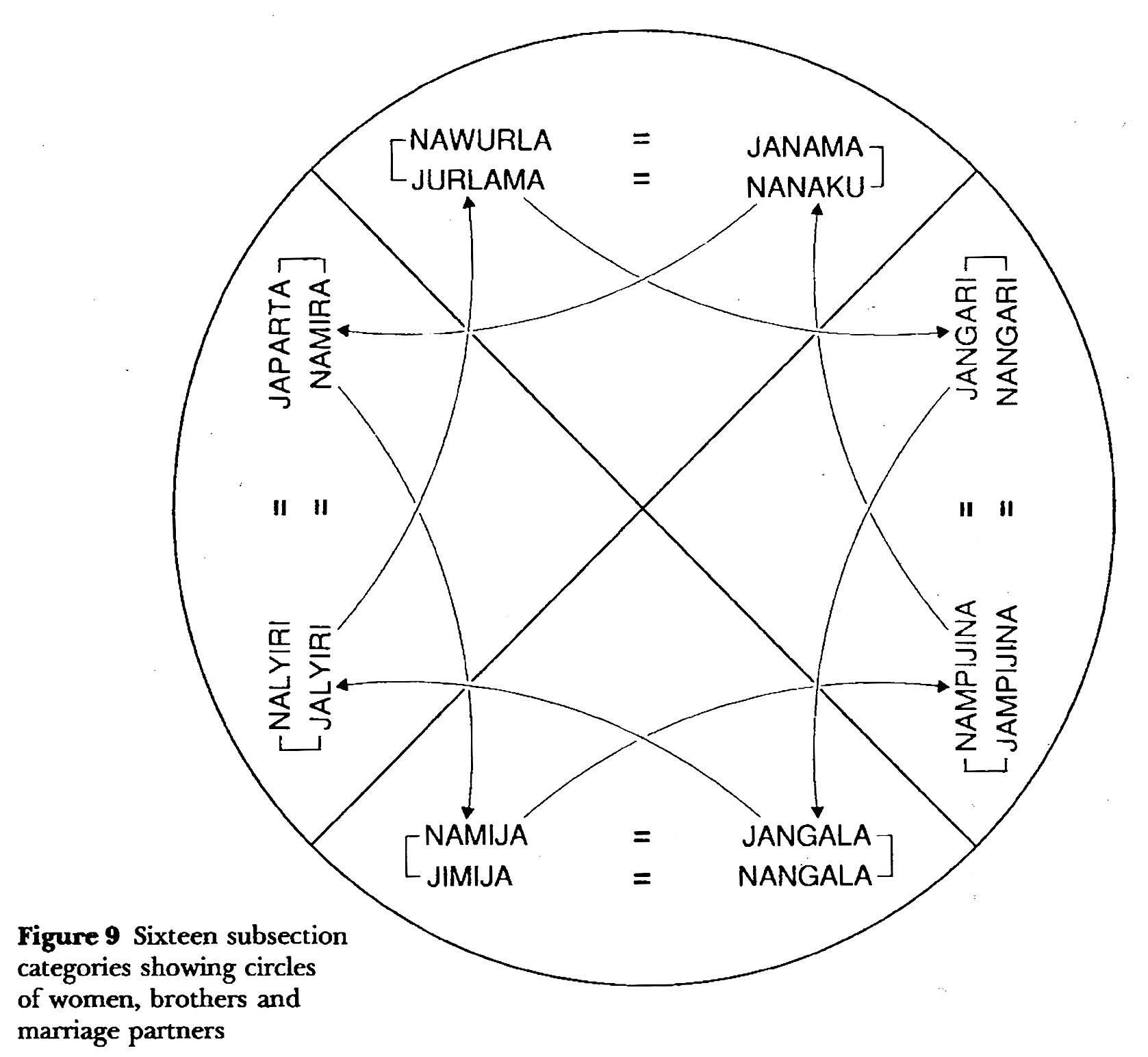

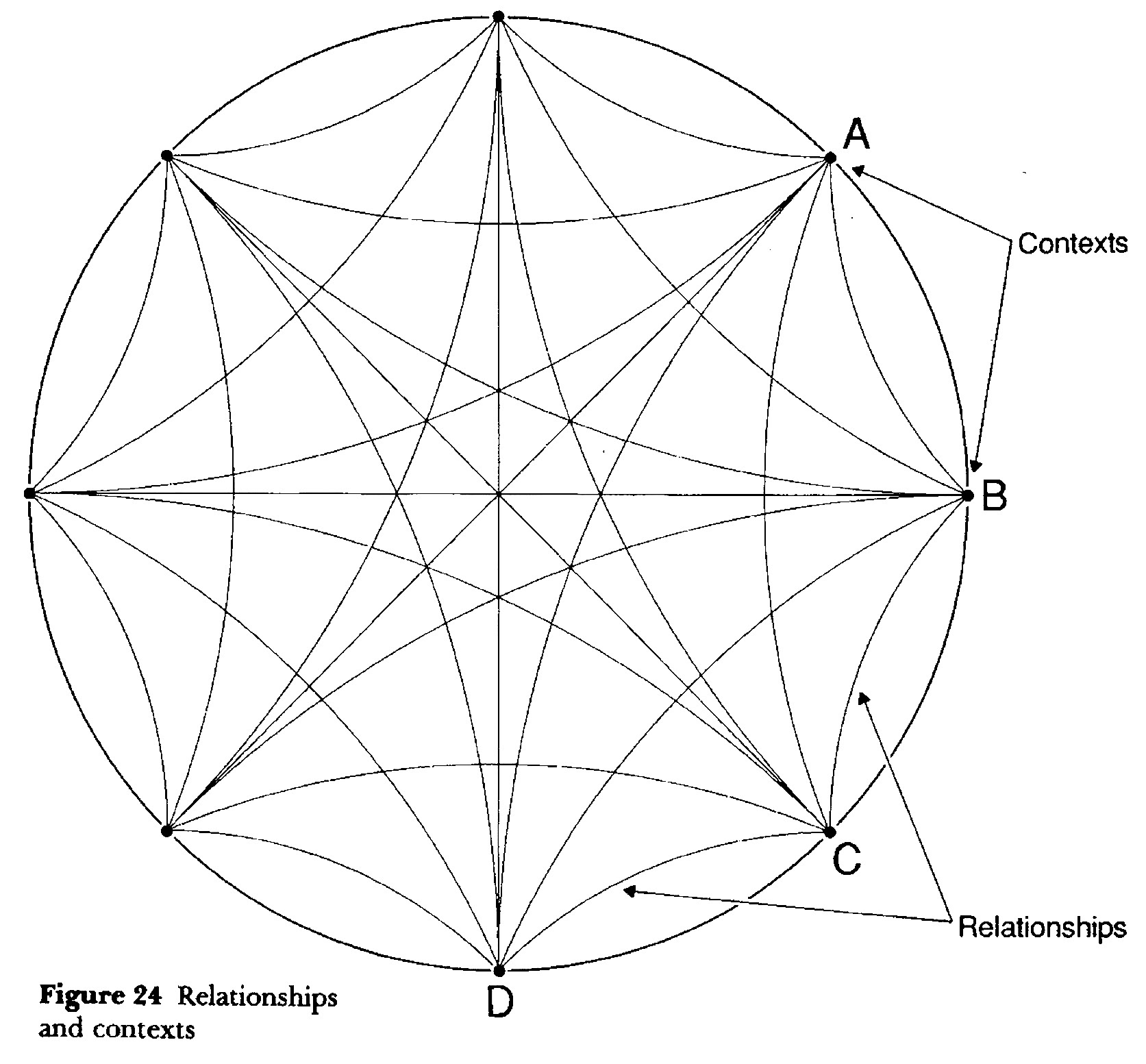

Figure 9 – Yarralin marriage practices and identities cross-cutting moieties and social categories Figure 24 – Relationships and Contexts

Rose, D. (2000 [1992]) Dingo Makes Us Human: Life and Land in an Australian Aboriginal Culture. Cambridge: University Press.

Rose, D. (2000 [1992]) Dingo Makes Us Human: Life and Land in an Australian Aboriginal Culture. Cambridge: University Press.

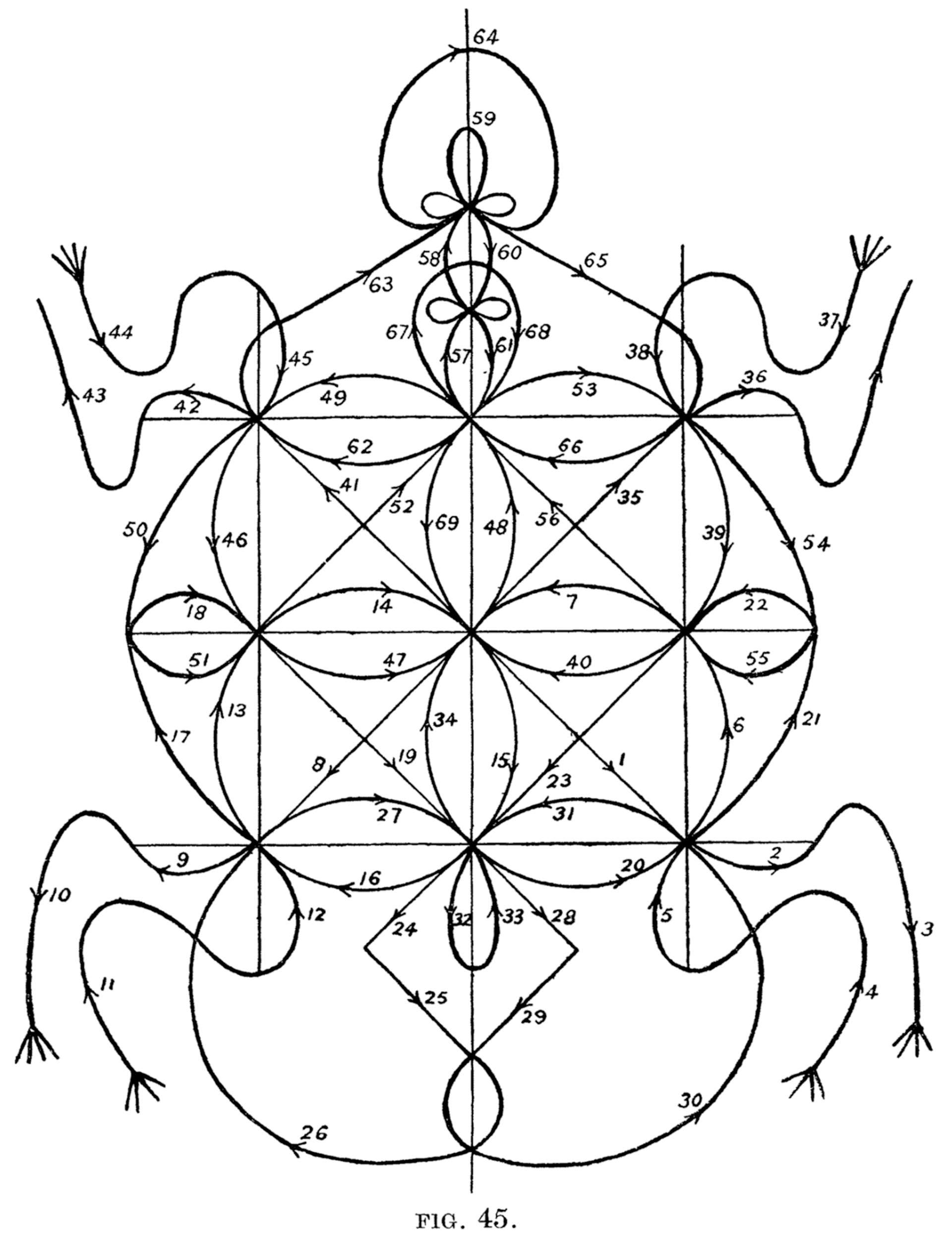

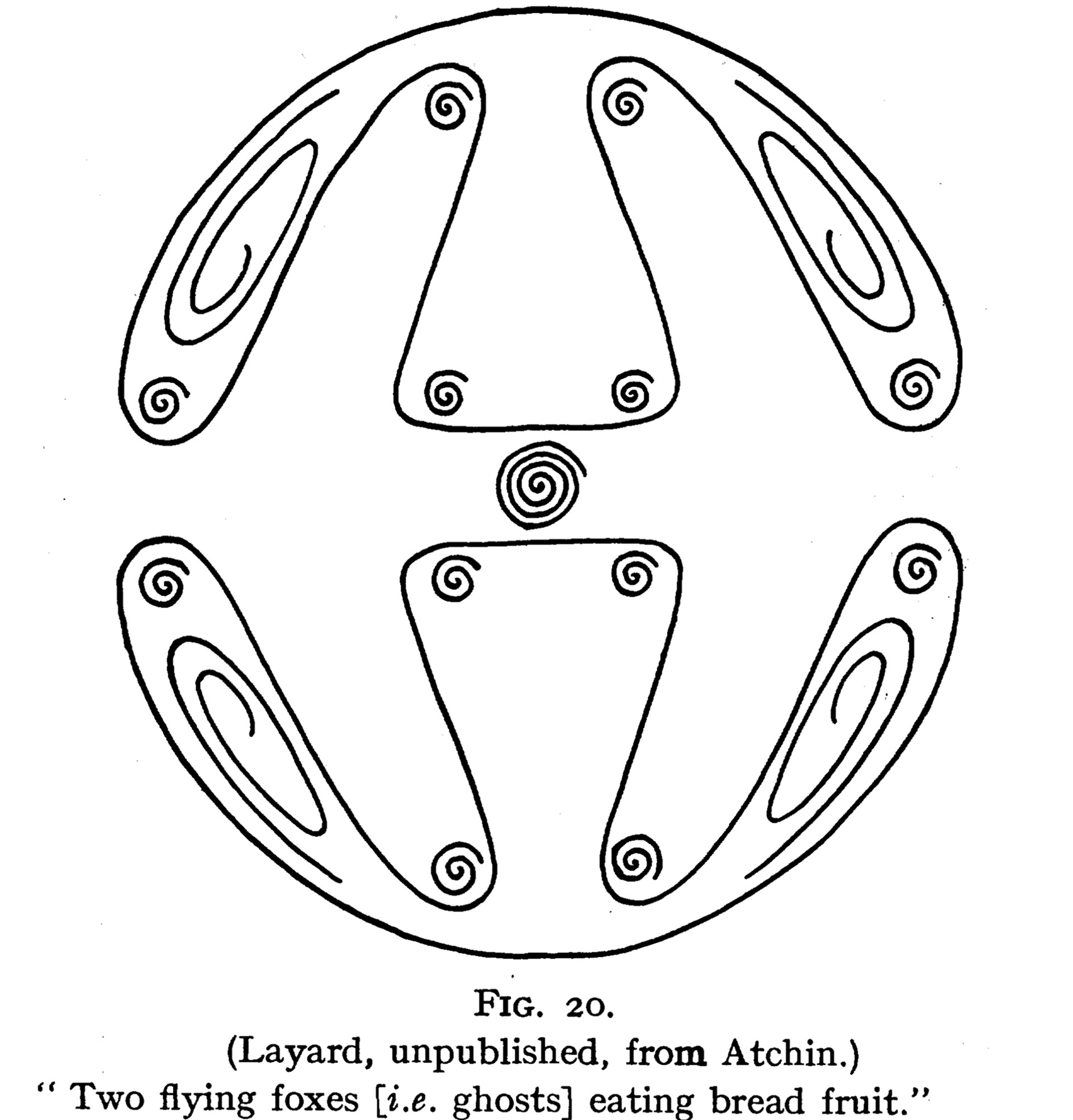

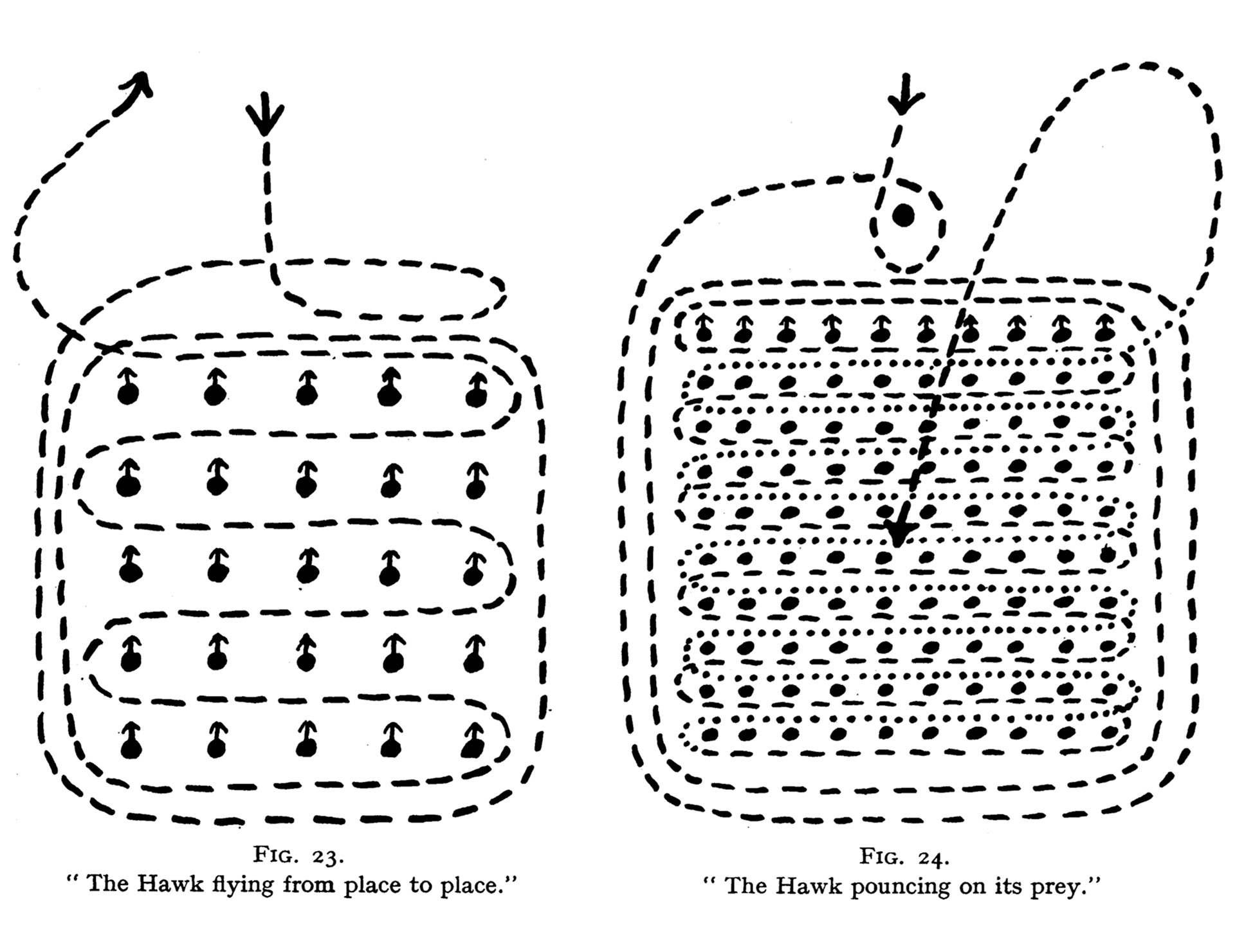

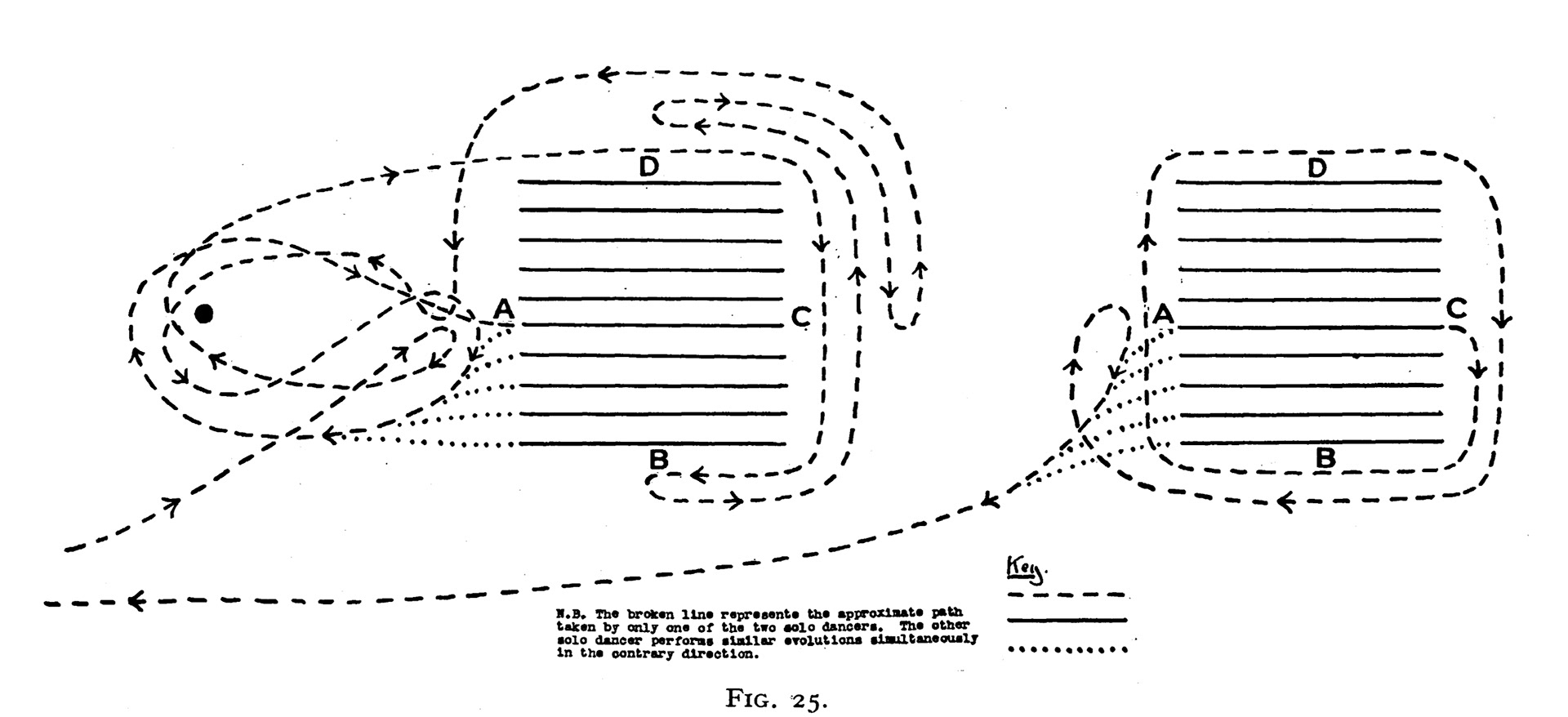

Layard, J., 1936. Maze-Dances and the Ritual of the Labyrinth in Malekula. Folklore, 47 (2), 123–170.

(Left) canoe types and construction (1922: 83/top; 85/bottom).

(Right) diagram use in linguistic work (1948: 261)

Malinowski, B. (1922) Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Quinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Malinowski, B. (1948) Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Glencoe, Illinois The Free Press.

(Right) diagram use in linguistic work (1948: 261)

Malinowski, B. (1922) Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Quinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Malinowski, B. (1948) Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Glencoe, Illinois The Free Press.

(Left) Gell (1999: 64) and an ‘impossible figure’ to reflect the symbolic practices of marriage and affinity.

(Right) Another ‘Strathernogram’ from Gell (1999: 72) detailing clan working and feeding relations.

Gell, A. (1999) The Art of Anthropology. LSE Monographs on Social Anthropology, col. 67. Oxford: Berg.

(Right) Another ‘Strathernogram’ from Gell (1999: 72) detailing clan working and feeding relations.

Gell, A. (1999) The Art of Anthropology. LSE Monographs on Social Anthropology, col. 67. Oxford: Berg.

(Leach 1961, at Ingold 2007: 112)

Kinship Diagram as Circuit Board

“The lines of the kinship chart join up, they connect, but they are not lifelines or even storylines. It seems that what modern thought has done to place – fixing it to spatial locations – it has also done to people, wrapping their lives into temporal moments” (Ingold 2007: 3).

Leach, E. (1961) Pul Eliya: A Village in Ceylon. A Study of Land Tenure and Kinship. Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, T. (2007) Lines: A Brief History. Oxford: Routledge.

Kinship Diagram as Circuit Board

“The lines of the kinship chart join up, they connect, but they are not lifelines or even storylines. It seems that what modern thought has done to place – fixing it to spatial locations – it has also done to people, wrapping their lives into temporal moments” (Ingold 2007: 3).

Leach, E. (1961) Pul Eliya: A Village in Ceylon. A Study of Land Tenure and Kinship. Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, T. (2007) Lines: A Brief History. Oxford: Routledge.

Evans-Pritchard’s (1940) diagrammatic lineage trees of the Jinaca (196/l) and Gaatgankiir (197/r).

Evans-Pritchard adapted the visual metaphor of the tree to account for such notions of scale in the inter-relationships between Nuer clans and lineages. He also made attempts to represent Nuer descriptions and depictions of these inter-relationships.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940) The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford University Press.

Evans-Pritchard adapted the visual metaphor of the tree to account for such notions of scale in the inter-relationships between Nuer clans and lineages. He also made attempts to represent Nuer descriptions and depictions of these inter-relationships.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940) The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford University Press.

(Left) Evans-Pritchard’s (1940: 201) outline of a Nuer system of lineage, compared with (Right) “how the Nuer themselves figure a lineage system” (1940: 202).

“[the Nuer] do not present [lineages] the way we figure them as a series of bifurcations of descent, as a tree of descent, or as a series of triangles of ascent, but as a number of lines running at angles from a common point… they see [the system] as actual relations between groups of kinsmen within local communities rather than as a tree of descent, for the persons after whom the lineages are called do not all proceed from a single individual” (Evans-Pritchard 1940: 202).

“[the Nuer] do not present [lineages] the way we figure them as a series of bifurcations of descent, as a tree of descent, or as a series of triangles of ascent, but as a number of lines running at angles from a common point… they see [the system] as actual relations between groups of kinsmen within local communities rather than as a tree of descent, for the persons after whom the lineages are called do not all proceed from a single individual” (Evans-Pritchard 1940: 202).

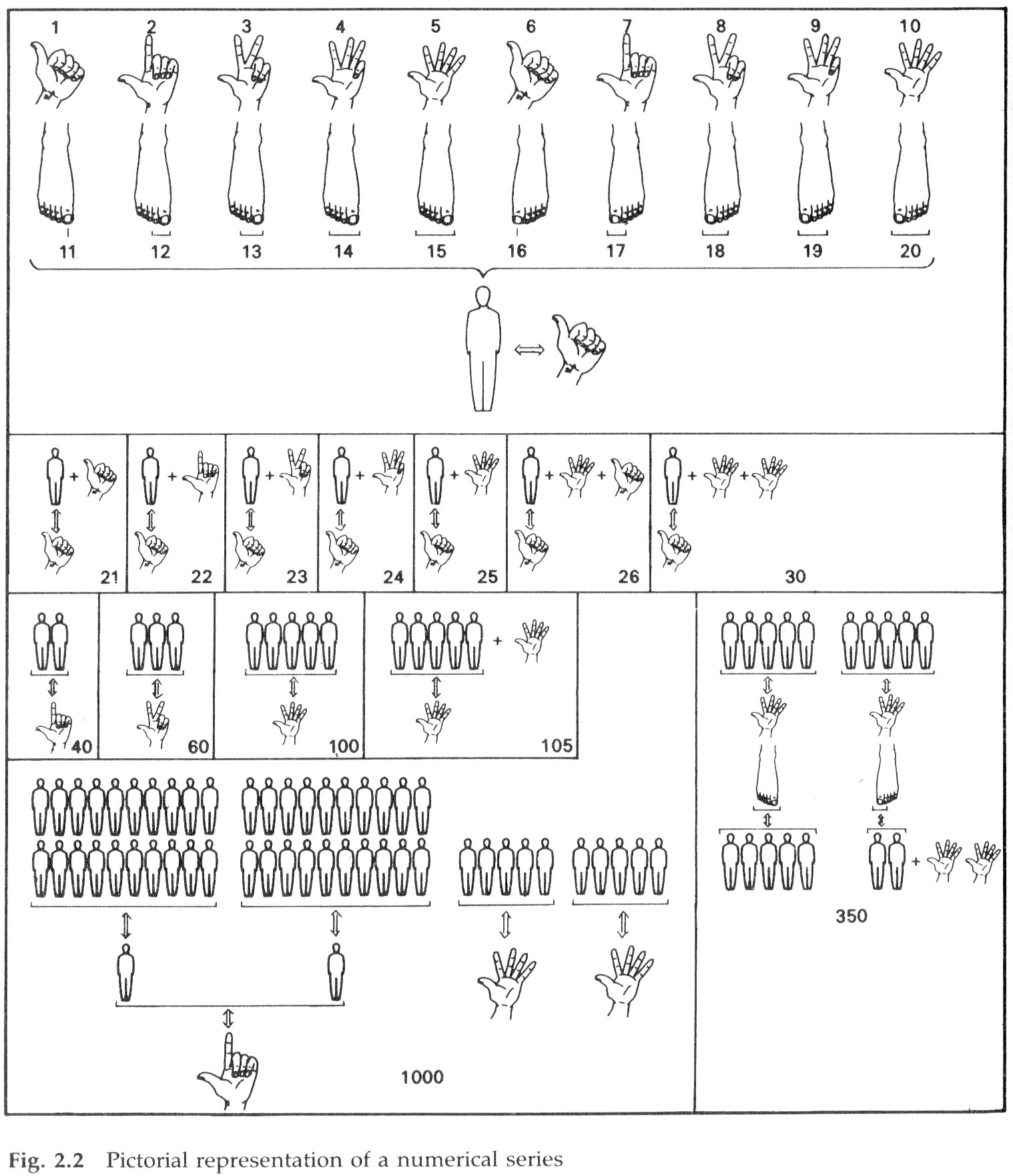

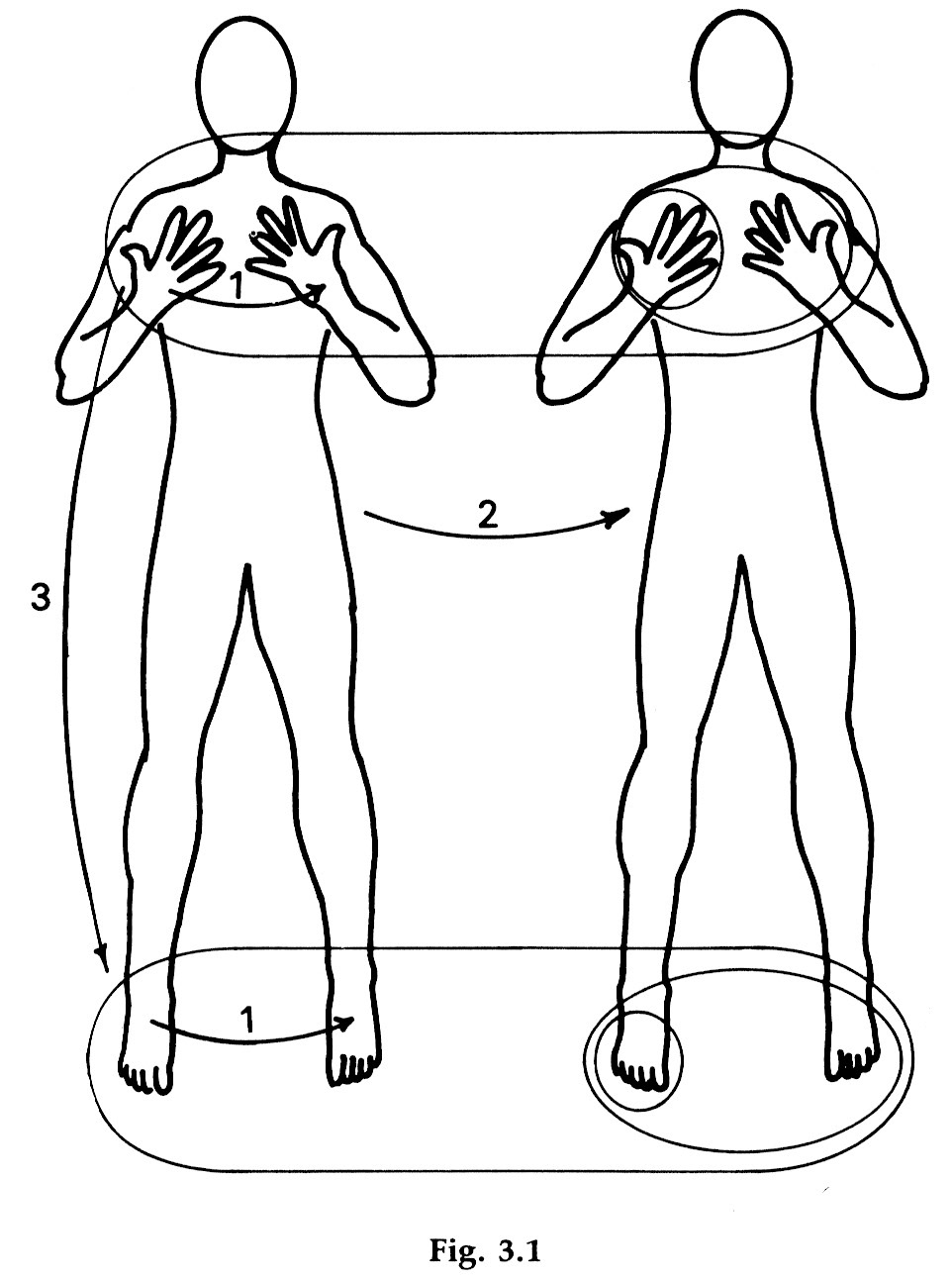

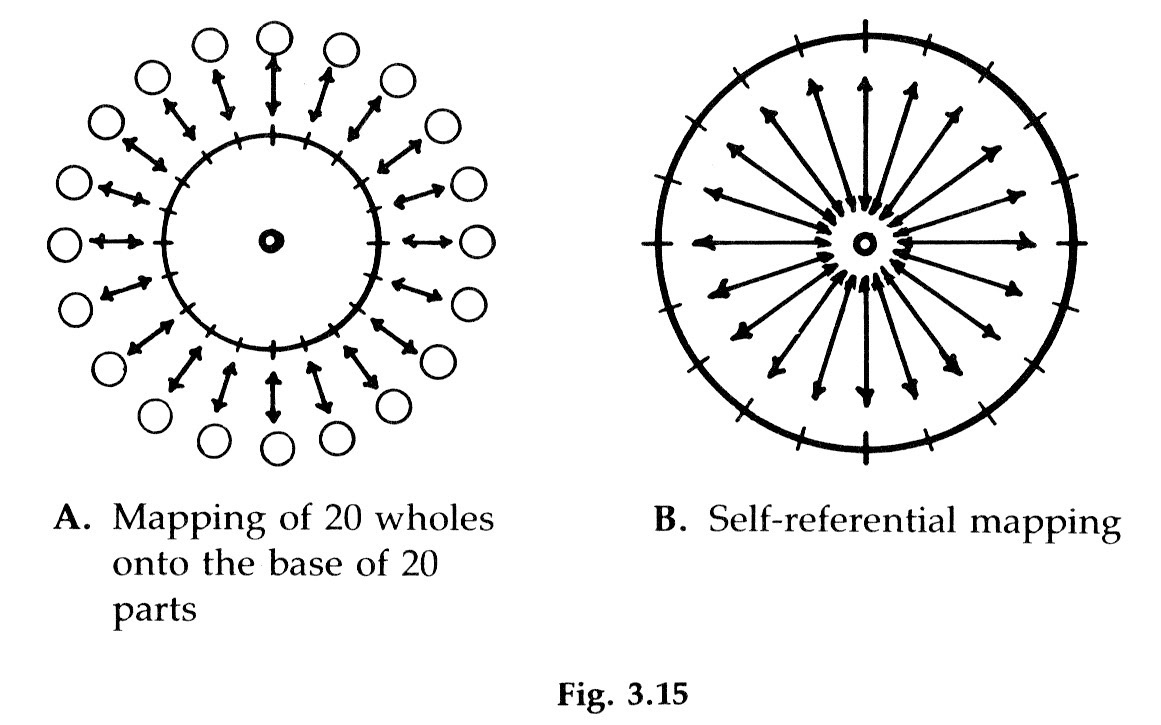

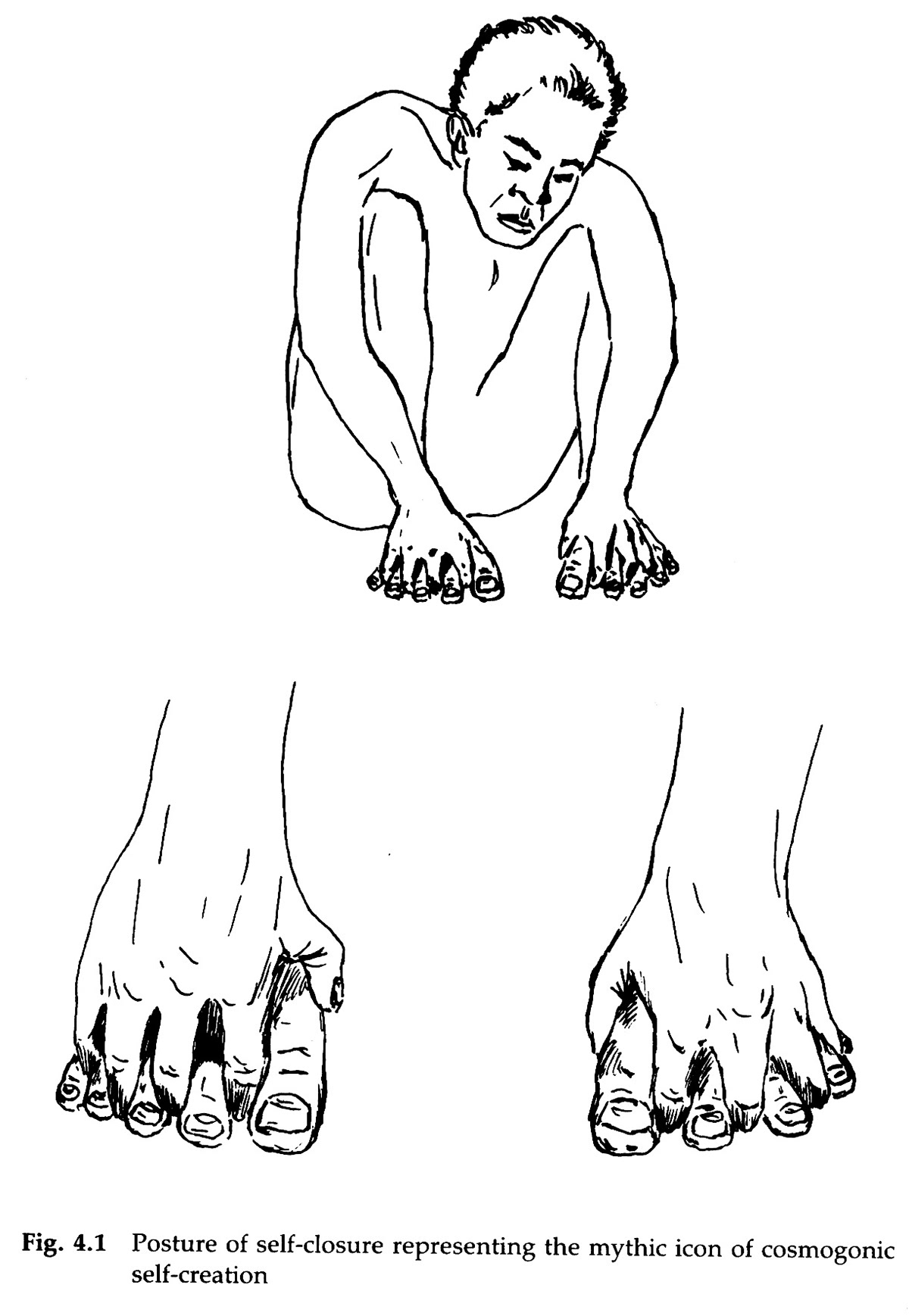

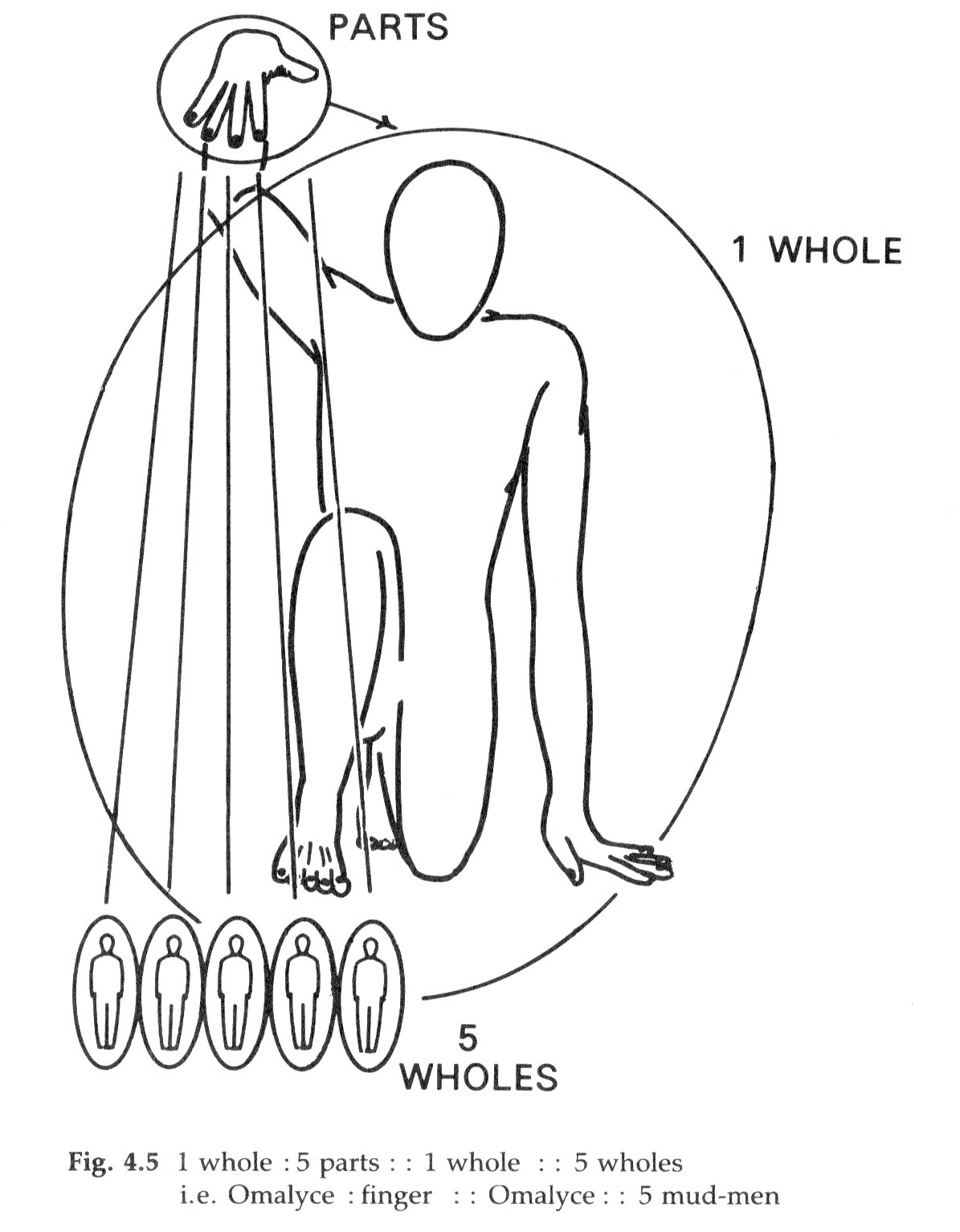

Mimica, J. (1988) Intimations of Infinity: The Cultural Meanings of the Iqwaye Counting

System and Number. Oxford: Berg.

System and Number. Oxford: Berg.

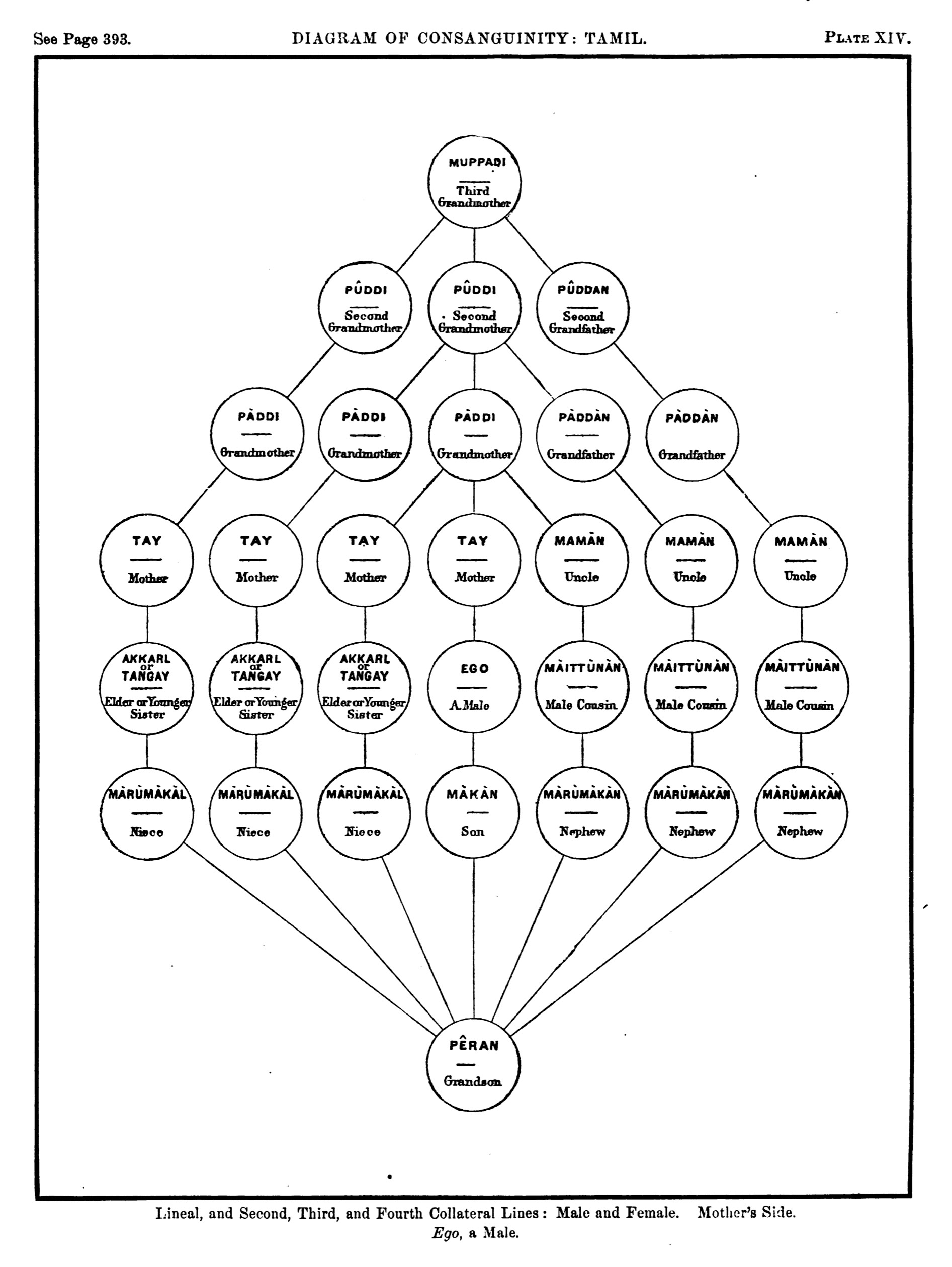

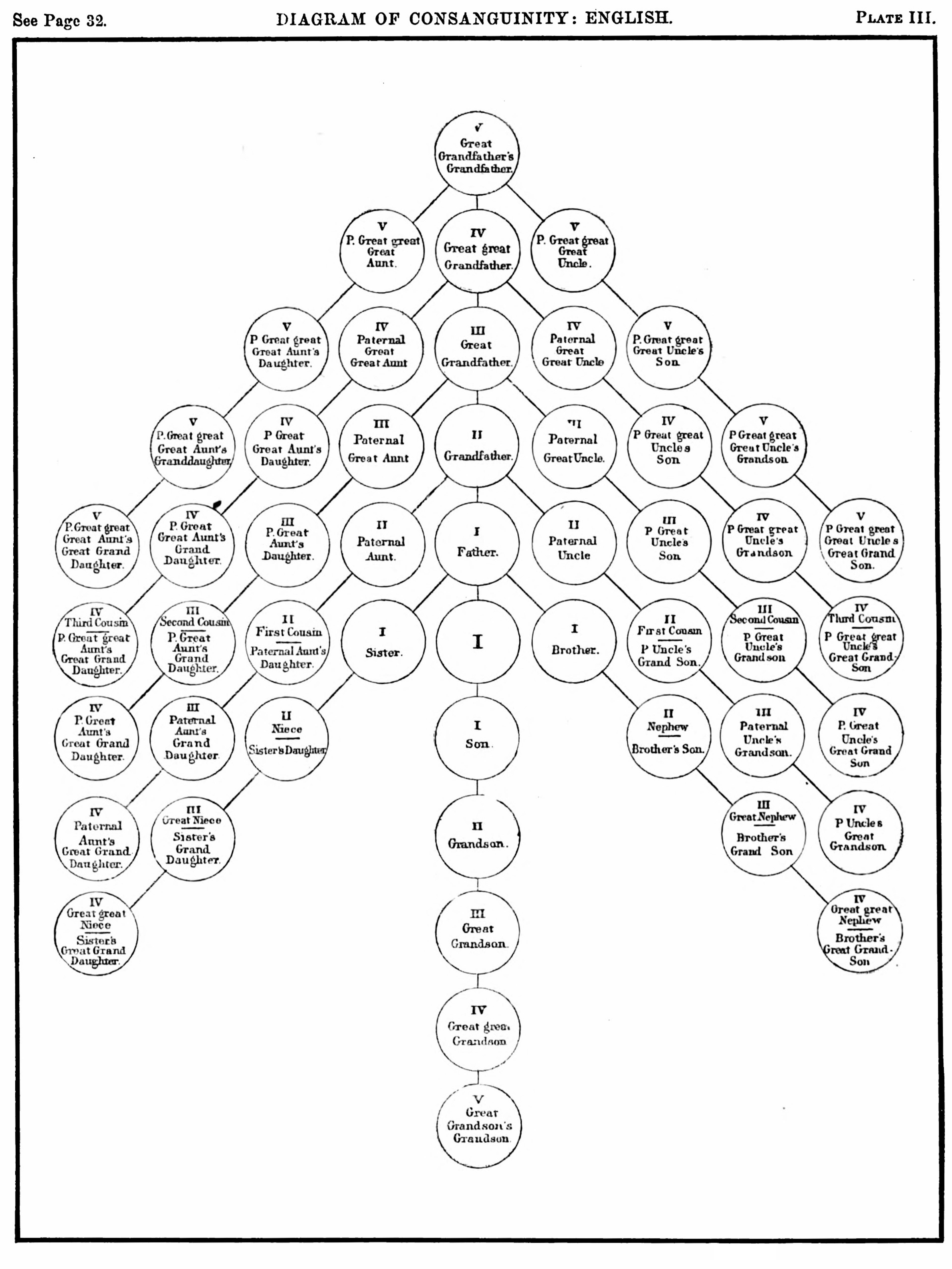

Two of Morgan’s (1871) ‘diagrams of consanguinity’

Morgan, L. H. (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Morgan, L. H. (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Munn, N. (1986) The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim Society. Cambridge University Press.

W.H.R. Rivers (1910: 1)

The Genealogical Method

...a ‘staunchly positivistic approach’ (Stocking 1992: 34)

...Rivers’ diagrams led to the conventionalisation of inverting the ‘tree’ of family trees,

placing ‘its roots at the top’ (Bouquet 1995: 42–3)

The Genealogical Method

...a ‘staunchly positivistic approach’ (Stocking 1992: 34)

...Rivers’ diagrams led to the conventionalisation of inverting the ‘tree’ of family trees,

placing ‘its roots at the top’ (Bouquet 1995: 42–3)

left: vol. I (p.177); illustration 136/5 – “Hand face” design 1.

right: vol. I (p.177); illustration 136/6 – “Hand face” design 2.

Steinen, Karl von den (1925) Die Marquesaner und ihre Kunst, 3 vols. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsem).

right: vol. I (p.177); illustration 136/6 – “Hand face” design 2.

Steinen, Karl von den (1925) Die Marquesaner und ihre Kunst, 3 vols. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsem).